Longread

Living labs are all the rage, but what are the success factors for a sustainable transition?

WUR and other knowledge institutes study sustainable agriculture, production chains and cities. But how does this research make a sector or system more sustainable? Living labs are used to incite transitions. What are living labs, and what are the success factors? A conversation on power, co-creation, trust and reflexive monitoring.

Barbara van Mierlo, a researcher with WUR’s Knowledge, Technology and Innovation group, contributes to the CropMix research programme in the domain of design and support for living labs. They intend to experiment with strip-tilling in the Netherlands. Among those invested in these living labs are crop farmers, a supermarket, officials of the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Safety (Dutch acronym LNV), allotment gardeners, a bank and the Butterfly Foundation—a varied group of stakeholders.

Platform for co-creation

‘We are not a research programme, but a co-creation platform in which everyone has an equal role’, Van Mierlo says. That means that the researchers, too, must change. They would typically focus on excellent research and publications, but their role within this consortium is to help develop transition pathways towards ecological agriculture. ‘Such transitions means learning to deal with fundamental uncertainties about what agroecological agriculture is, what part strip-tilling can play, and how to bring about ecological agriculture’, Van Mierlo states.

We are a co-creation platform in which everyone has an equal role.

Strip-tilling includes tilling in strips as wide as 24 meters or as narrow as one meter and a mix of crops and food forests. Van Mierlo proposes establishing three or four living labs to explore different options.

The groups are focused on action, Van Mierlo says. A CropMix group will probably test how to organise supplying local foodchains with crops, with the matching logistics and its own philosophy. Another group will explore possibilities for strip-tilling, which is better aligned with the current food markets. That group will also encounter challenges, such as covering the additional costs of strip-tilling.

What is a living lab?

A living lab is a location where different parties achieve a joint understanding of a complex problem and collaborate towards knowledge development, says Kris Kok, a researcher with the VU University of Amsterdam’s Athena Institute. Moreover, a living lab experiments with solutions, thus testing whether a problem can be solved through technical, managerial and socioeconomic innovations. Kok researches and is involved in different living labs focusing on sustainable food systems.

The problem must be leading, Kok says. It also provides the living lab with structure. A living lab has a method and rules. First, a living lab has walls; the participants decide which parties are included and which are excluded. That is far from easy, as the problem must be both specific and complex. One party contributes from a health perspective, the other from biology, and a third from economics. What parts of the problem will you address, and what aspects will you exclude? ‘That is a question that must be answered explicitly’, Kok states, ‘that is based on political consideration which will lead to questions.’

Overturning the balance of power

Secondly, there is a method for living labs. Process counsellors ensure structured dialogues and workshops in which everyone has the opportunity to voice their opinion; participants question and challenge each other, and dominant players leave sufficient room for others. This is where the term “reflexive monitoring” pops up.

Kok explains that it comes down to bringing people involved in a system or sector (health care or the food chain, for example) together in a lab and ensuring that civilians can discuss with CEOs and council members on equal terms. By overturning the balance of power, you extract yourself from the present situation and routines, seeking innovation. During the search to change the system, you discover the rules of the system and arrive at transition pathways to innovate, for example, food systems and health care.

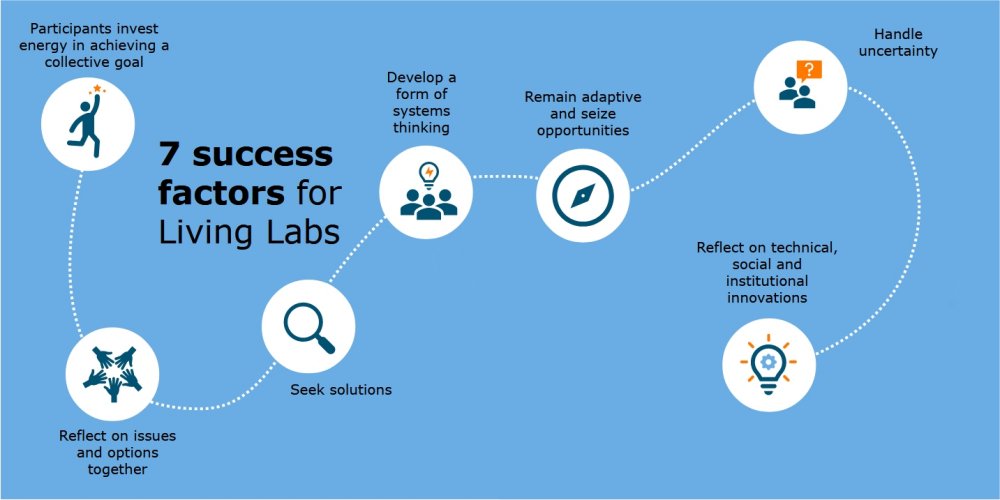

Seven requirements for a successful living lab

Learning is, hence, essential in transitions. WUR’s Barbara van Mierlo specialises in interactive learning. She developed the Reflexive Monitoring in Action approach in collaboration with other researchers. This approach serves to monitor the learning process within a living lab. The sociologist applies this method to all sorts of initiatives in the domain of sustainable agriculture, health, nature and environmental education and sustainable energy.

- The participants are willing to invest energy in achieving a collective goal with others;

- They believe that reflecting on issues and options together is useful;

- They seek solutions for the obstacles they encounter within themselves or the dominant system through a step-by-step approach;

- They develop a form of systems thinking. What rules are there, how are they connected, and how much room is there for innovation?

- They are adaptive, have adaptive capacities and seize opportunities as they present themselves;

- They are able to handle uncertainty. The outcome is not fixed. The participants must explore and test without a structured plan; the group is their only footing, and the process is a future possibility;

- They reflect on technical, social and institutional innovations. Not just technology but also other rules, values and processes.

Although the participants seek solutions together, they need not have a common perspective, Van Mierlo states. ‘In CropMix, Albert Heijn’s perspective differs from that of the farmers and allotment gardeners, and that will remain so. The goal is to learn from each other, see the connections and overcome obstacles by finding answers together.’

Living labs occur in many different forms. Some labs focus on production or distribution issues in a particular sector that develops a business model to bring new products to the market. Other labs seek to embed sustainable technology in society, while still others work on profound transitions such as fossil-free production.

A living lab may also overcome barriers between researchers and participants, Marleen Onwezen of Wageningen Economic Research says. ‘We are currently doing a project on healthy eating habits among consumers with limited socioeconomic status. We believe that finding answers together works really well for this group of consumers, who are ordinarily difficult to reach. I believe this may be credited to the engagement and commitment of the researchers in this living lab. Something is happening between researchers and consumers; there is a joint effort being made. That may well cause this group to feel heard.’

Collaboration between civilians and scientists within a living lab is not always successful. ACCEZ, a network of university researchers, businesses and local administrations such as the province of Zuid-Holland, created a living lab in Binckhorst, a neighbourhood in The Hague. Their goal was to explore circular initiatives among businesses and residents. The Hague municipality intended to make this neighbourhood, which is characterised by old industrial lots, 50% circular by repurposing materials and generating sustainable energy. The Knowledge Workshop in Production (KWP) enabled researchers to exchange ideas with, among others, car garages, a local hops grower and beer brewer, an asphalt factory and a waste processer who all operated within circular networks beyond the perspective of the circular neighbourhood. The development thereof rested with project developers who tore down old buildings to create 5,000 new homes. The resulting rent hike even caused some of the circular businesses to move.

Real influence and participation require political support.

Researcher Marleen Buizer of WUR’s Strategic Communications group analyses what went wrong. According to her, the living lab identified the neighbourhood’s problems and wishes but was insufficiently connected to the municipality and project developers. ‘We exchanged views on how the neighbourhood might develop towards circularity with the municipality and project developers in interactive sessions. However, not a single official in the municipal council was responsible for this issue. Real influence and participation require political support that goes beyond the short-term project. Otherwise, you may find yourself designing a transition while the outcome is not secured, with disappointment as a result.’

Political support

The head of Wageningen Environmental Research’s Green Cities programme, Marian Stuiver, acknowledges that political support is important. This Wageningen sociologist contributes to Green Circles, a network of innovative businesses, knowledge institutes, administrations and civic organisations in Zuid-Holland. Green Circles celebrated its ten-year anniversary last month. In one of its living labs, farmers in the Alblasserwaard work with WUR and Naturalis to find ways to increase biodiversity on their land. In addition to measuring biodiversity, they experiment with different soil and nature management forms on their farms, enabling them to upscale successful practices.

Stuiver: ‘Political backing by the province is important. There is always a Provincial Executive involved in the Green Circles living labs. Does that have an impact? After Friesland, Zuid-Holland has the highest agricultural participation in nature management. And although the numbers fluctuate, a slight increase was reported after 2016. I am confident in saying that Green Circles has succeeded in increasing support for agricultural nature management in Zuid-Holland from one or two decades ago.’

Most living labs have only been around for a few years; it is too soon to determine whether they contribute to a sustainable future. ‘Moreover, it is difficult to assess the influence of a concrete initiative on making an entire sector more sustainable’, Van Mierlo says. However, she adds that advancement within a transition can be recognised, as her reflexive monitoring aims to do. For example, the emergence of new collaborations, overcoming obstacles, achieving the preconditions for innovation and real changes in people’s values.’

Living labs set the agenda for the future.

Stuiver also sees results. ‘Because parties are brought together, a dynamic is created. Particularly when you design alternatives for the current situation. WUR colleagues are currently developing nature-inclusive solar parks within a project, for example. Here, parties collaborate to combine energy generation and biodiversity within a zoning plan. The government will include this in its design brief, which will give the project developers involved in the living lab a headstart. Thus, living labs set the agenda for the future.’

Sustainable futures

WUR works on sustainable futures. This entails climate-neutral food systems and landscapes that benefit biodiversity. This is the 5th episode in the series Shaping Sustainable Futures.