News

Wageningen self-test for brain damage wins silver in student competition

During the annual SensUs Challenge, a team of students from Wageningen University & Research has developed a self-test for non-congenital brain damage, which limits the need for expensive imaging scans. The team, known as SenseWURk, claimed second place during the finals of the competition at the beginning of September.

The SensUs Challenge is an international student competition hosted by TU Eindhoven. It challenges students from across the globe to develop novel biosensors for healthcare applications. Each year, the competition centres on a distinct health-related challenge. In the current edition, participating student teams were tasked with creating a diagnostic test for non-congenital brain damage, including conditions like concussions. Their mission was to craft a compact, swift, and user-friendly test, reducing the immediate reliance on costly CT or MRI scans. The Wageningen team achieved this ambitious goal. "This feels very special,” stated team leader Sifre van Teeffelen.

Testing with a Drop of Blood Plasma

The Wageningen self-test operates on a concept reminiscent of a COVID-19 self-test: a small blood sample is applied to the end of a paper strip, and shortly after, a line appears if brain damage is detected. The test identifies the presence of a specific biomarker, GFAP (Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein). Van Teeffelen explains, "GFAP is a protein typically found in the brain, but following head trauma these substances find their way into the bloodstream." Hence, when GFAP is present in a patient's blood, it indicates brain damage. The severity of the damage is proportional to the concentration of this biomarker.

Guiding a team of highly motivated students in the development of this test was a rewarding experience

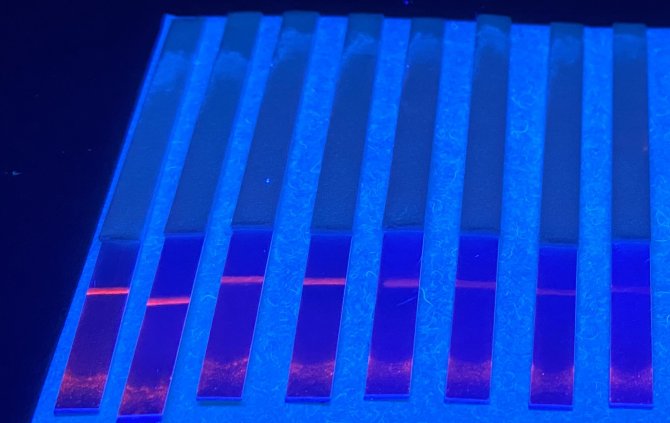

To detect GFAP, the students employ an antibody, much like those used in COVID-19 self-tests. However, in this case, the antibody does not capture viral particles but rather the brain-specific chemical, GFAP. Van Teeffelen elaborates, "We applied the antibodies in a linear pattern onto the paper strips using a specialised machine. When blood flows along this border, antibodies capture the brain protein. A secondary antibody, tagged with a fluorescent nanoparticle, binds to the GFAP, creating a fluorescent sandwich-like structure. This enables us to use a UV lamp in a specialised device to determine the presence and extent of GFAP."

The Crucial Test

Over the course of six months, the students meticulously constructed and tested their biosensor. However, the ultimate test awaited them during the final week of the competition. Each participating team had the challenging task of conducting measurements with their biosensors. Van Overbeek emphasises, "The test not only has to diagnose brain damage, but also assesses its severity." During the finals, every team had two hours to analyse 24 blood samples, each representing a different level of brain damage. The Wageningen students' biosensor demonstrated accuracy in this crucial task. Only the team from Portugal managed to measure the values more accurately with their device.

While the long-term vision is to perform the self-test using fresh drop of blood, so far the students have only used one part of blood known as plasma. Plasma is devoid of red and white blood cells, as well as platelets, It primarily consists of water and proteins, including GFAP. Van Overbeek underscores, "Blood flows differently through paper than water or blood plasma, so adjustments may be necessary if the test is to operate with blood samples in the future."

Reality Check

The Wageningen students are proud of their second-place achievement. Their mentors also applaud their dedication and work. "Guiding a team of highly motivated students in the development of this test was a rewarding experience,” says supervisor Aart van Amerongen (Wageningen Food & Biobased Research). “Their success is undoubtedly the crowning achievement of the joint efforts."

However, for the time being, the self-test is not ready for immediate deployment in hospitals. The students' current priorities lie in their academic pursuits, thus the project will not immediately result in a startup. Nonetheless, the competition has bestowed valuable experiences upon the students. Van Teeffelen reflects: "During a laboratory practicum, students follows a meticulously designed protocol, but here, we began with just an idea and had to forge our own path. That did not always go well and in the process the students learned to correct mistakes and adjust their plans.

It is a nice reality check: research seldom goes according to plan.

For Van Overbeek, the SensUs competition was an opportunity to step out of her comfort zone. "Typically, I focus solely on my studies, leaving little room for extracurricular endeavors," remarks the master's student. This is precisely why she seized the chance to collaborate within a team on a unique project. The payoff has been substantial. "This experience has contributed significantly to my personal growth and it is also a nice reality check: research seldom goes according to plan."

Do you want to join SensUs next year?

Are you interested in joining the Sensus 2024 challenge? Please contact Johannes Hohlbein for more information.