Longread

Wind farm or nature reserve?

The intention is that by 2050, the North Sea will be Europe’s green power station. That will require ten times as many wind farms as there are today. Research is aimed at revealing what all those turbines will do to the ecology of the nature reserve. ‘What makes it a bit worrying is the fact that construction of the wind farms is already in full swing.’

Text: Rob Buiter | Infographics: Kay Coenen

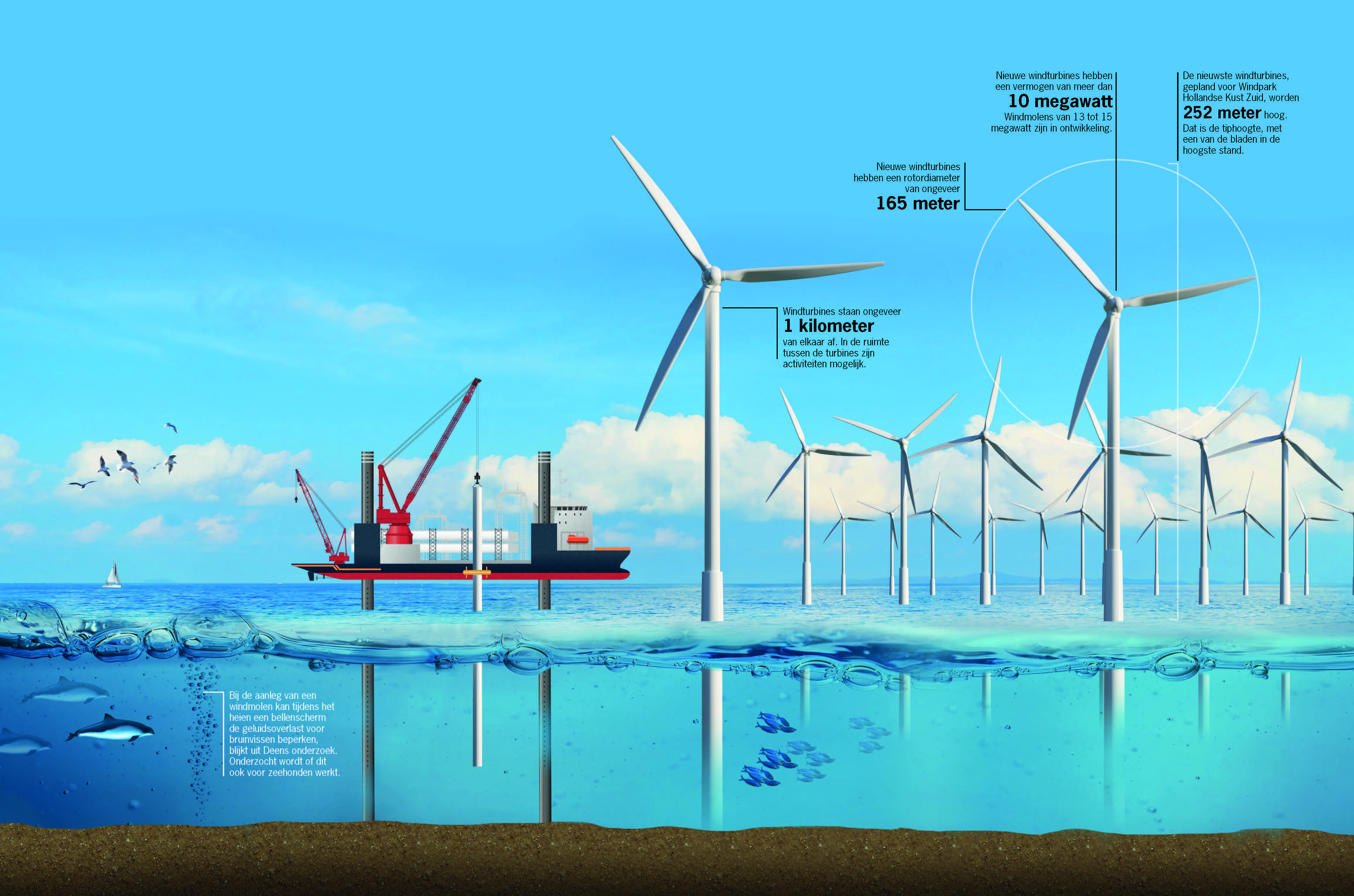

On a clear day, you can already see them from many places along the Dutch coast: wind turbines of more than 150 metres in height. They are also visible on a clear night, incidentally, thanks to their synchronised flashing red warning lights. Already now, one of these modern turbines has a capacity of more than 10 megawatts. And the ambition expressed by the energy ministers of the North Sea countries – excluding Britain – of reaching 150 gigawatts of power by 2050 would require nearly 15,000 large turbines in the North Sea, or somewhat fewer if the capacity per turbine increases further.

The potential impact of so many turbines on the North Sea is massive, and not just on the view from the beach. That is why the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy launched the research programme WOZEP, the Wind at Sea Ecological Programme, in 2016. Wageningen Marine Research is one of the institutes carrying out the studies. Others include water and subsurface research institute Deltares and the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research TNO. “The key question for this programme is which legally protected species could clash with the ambitions for the energy transition,” says Josien Steenbergen, Offshore Wind research coordinator at Wageningen Marine Research. “This can refer to birds or bats that can literally collide with the turbines, but it can also be about effects on life below sea level.”

Birds and blades

The most visible potential victims of wind farms are birds. “But collisions between birds and blades are extremely difficult to establish at sea,” says marine ecologist Floor Soudijn of Wageningen Marine Research. “You hardly ever witness the collisions themselves. On land, you sometimes find the victims still lying beneath the turbine, but at sea that’s pretty much impossible too.” Research into the effects of wind turbines on birds is therefore dependent on the analysis of radar images, tagged birds and theoretical models.

Soudijn: “A lot of work is going into the development of those models. They start with probability calculations that treat birds like random particles in the air, but then they have to be optimised with data on the actual behaviour of birds.” The researchers are mapping the natural flight behaviour of birds using tagged lesser black-backed gulls. Soudijn: “The flight altitudes and speeds we measure can be used in calculating collision probabilities. Because we don’t have any data yet on tagged birds from colonies near wind farms, it remains to be seen how their flight behaviour changes when they approach turbines. But so far the evidence suggests that in the vast majority of cases these birds avoid the turbines and often in fact the wind farms in their entirety.”

Field observations wind farms

The most specific information is obtained from field observations near the wind farms. “Then we clearly see that many bird species keep out of the way of the turbines. Gannets in particular, but also guillemots, razorbills or the various divers: they all steer clear. This means they lose a bit of their usual habitat, but it would be hard to establish whether that means that the wind turbines also affect population sizes,” Soudijn said. On the other hand, there are also species that don’t seem very bothered by the turbines. “For cormorants, for example, it seems to be no problem to sit on the structures in a wind farm. Maybe these new perches further out to sea even offer advantages when they are fishing,” suggests Soudijn.

Sophie Brasseur of Wageningen Marine Research has been using adhesive transmitters to track seals in the North Sea and Wadden Sea for many years. At the behest of WOZEP, Brasseur and her colleagues have spent the past three years studying the behaviour of seals this way during the construction of the new Borssele wind farm, off the coast of Zeeland. “When this farm was under construction, a bubble screen was used around the pile-driving,” Brasseur says. “Danish research has shown that those bubbles in the water dampen the noise, particularly the higher tones. It is thought that porpoises especially suffer much less from the pile-driving as a result. But seals are sensitive to the low tones as well as the high ones. With our study we aimed to find out at what distance from the bubbles and at what volume seals are still bothered by the pile-driving.”

Impact on seals unclear

The results of the study were somewhat disappointing. “By which we mean that we couldn’t really draw clear conclusions, because for some reason seals seem to avoid this area with lots of wind farms anyway. And if there are no seals, it’s hard to measure effects,” Brasseur said. “At the same time, of course, this is an important pointer. There are already wind farms in our research area. So far, seal research has always been focused on the effects of construction, but we should also do research to find out whether animals stay away because of the existing parks. It is all very well to say that once wind farms are established, they will become a kind of reserve where no fishing boats are allowed and there is therefore more food for birds or marine mammals. But we have no evidence yet that seals will be attracted to that presumed extra food supply; in fact, the initial findings suggest the opposite.”

Because seals regularly come ashore, Brasseur and her colleagues can track population trends accurately. Of the 50,000 common seals counted on North Sea coasts, the majority, nearly 30,000, live in the international Wadden Sea. “Precisely this population has not been growing for a decade. In fact, its numbers have declined significantly over the past two years. I would very much like to rule out the recent construction of wind farms, mainly in Germany and Denmark, as the cause of this decline.”

Migratory bats

Besides birds, bats are sometimes hit by the blades of a wind turbine on their flight, or even by the air pressure waves around the blades. The corpses under wind turbines on land are a silent witness to this. But it can happen at sea too, argues Sander Lagerveld of Wageningen Marine Research. “For example, it has long been known from ringed bats that Nathusius’ pipistrelle bats migrate across the North Sea to Britain. We now have rather more high-tech ways of tracking the bats. The tiny 7-gram creatures – the weight of two sugar lumps – are fitted with transmitters weighing just 0.26 grams. Data from the transmitters is then collated using a network of 50 receiving stations along the Dutch coast and a few more in Belgium and in England.”

Lagerveld continues: “We detected a crossing of the sea by 15 bats tagged by the Norwich Bat Group in England. This is telling us things about the timing of their migration over the sea and the weather conditions under which it takes place.” The researchers also hung up 14 bat detectors at wind farms, on gas production platforms and on measuring islands in the sea. “The first surprise we got from the sound recordings was that the bats certainly don’t always fly across the sea in one go. We sometimes record bat sounds at the end of the night and just after sunset. That can only mean that they have spent the day on the platform, or perhaps on a nearby wind turbine or boat.”

In autumn, when some pipistrelle bats migrate from mainland Europe to the British Isles, most of them can be identified. They mainly seem to venture across the sea when there’s a moderate east wind, i.e. a tailwind. But some of them also migrate in crosswinds or even in headwinds of up to about five metres per second.

Lagerveld does not rule out that bats will even migrate in stronger tailwinds. “Only we don’t pick them up on the detectors. I suspect that, like migratory birds, they fly at higher altitudes at such times. But we don’t know whether that is then still within the range of the rotor blades. So it would be good to do more research to find out exactly how high the animals fly over the North Sea.”

At the wind farm near Borssele, measures have been taken to protect flying birds and bats. Lagerveld: “Computer models use radar images to predict the peak in bird migration, and at that point the turbines can be shut down. The turbines are also stopped during the bat migration period when there’s a light east wind, but at present that doesn’t coincide precisely with the behaviour we are seeing. There is also a risk of collisions with bats in crosswinds and headwinds, and probably in strong tailwinds too. It is very important to know at what altitude the bats fly during different wind conditions. We need to research that better.”

Optimising rocky bases

Things that are positive for nature seem to happen underwater in wind farms too, says Oscar Bos of Wageningen Marine research. “You put a hard substrate in a place where there used to be only sand. In pilot projects in the first wind farms, one of the things we are looking at is whether these are good places to bring back the flat oyster reefs that have vanished from the North Sea. We are also looking at how to optimise the mix of rocks deposited at the base of the turbines as erosion protection, to create a reef where top predators such as cod can take refuge as well. So the wind farms also bring opportunities with them for additional ecosystems.”

Bos is not expecting major ecological shifts, however. “At the locations where wind farms are planned, there is usually only sand at the moment. But there are many thousands of wrecks in the North Sea. So ‘artificial ecosystems’ like the ones we will be adding already exist at various locations.”

Balancing ecological risks

Broadly speaking, some initial conclusions can already be drawn from the ecological research, but at least as many questions remain to be answered. “Actually, we are collecting a big bowl full of apples and oranges,” concludes research coordinator Steenbergen. “Because how do you balance the interests of a gannet that has to avoid a wind farm against those of a flat oyster that might get new opportunities there? And even trickier: how do you balance the ecological risks against the sorely needed gains in renewable energy, and how do you balance that against the losses of fishermen, whose trawlers are not allowed into the growing number of wind farms? Research is ongoing into whether alternative forms of food harvesting are possible within the wind farms, for example using static gear (like gill nets, pots and longlines) instead of towed nets, or in the form of seaweed farms or mussel farms. Fortunately, these are all issues for politicians to decide on.”

“What makes it a bit worrying,” says Steenbergen, “is the fact that construction of the wind farms is already in full swing. Eight years can go by between the moment a wind farm is designated and when the last plug is connected. If we discover major ecological problems now, you can’t just say ‘we’re stopping’ without costing the taxpayer vast sums of money. Needless to say, you don’t want your ecological research to be redundant because the processes in question are already under way.”

Adaptive approach

One thing at least is clear: there is no shortage of attention being paid to ecological research. The WOZEP programme, implemented by the Directorate-General for Public Works and Water Management on behalf of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, will enter a second phase in 2024. And 2023 will also see the start of the Monitoring Research-Nature Enhancement-Species Protection programme, MONS for short. Steenbergen: “That programme will examine the ecological carrying capacity of the North Sea and the effects of the energy and food transitions on North Sea nature. MONS takes an adaptive approach. That means that the plans for wind parks should always be adaptable in light of the latest ecological insights.”

Steenbergen also points out that a recent tender for the construction of the Hollandse Kust (west) wind farm included an additional requirement. The government specifically asked for innovative ecological plans to be included in the project, thus handing some of the responsibility back to the operators. “And they might have some great ideas,” she says. As an example, land-based wind turbines are already fitted with smart cameras that stop a turbine when the computer sees that a bald eagle is approaching. “We want to use such innovations at sea as well, to ensure that the ecological knowledge that’s gathered gets incorporated.”